My project, The Flux, took as its inspiration Toronto’s inner city neighbourhood Regent Park. My conceptualization of the neighbourhood is informed by scholarly research I endured in the fall of 2015, as well as ethnographic experiences I had there in the mid 2000s. As such, The Flux holds these understandings, as well as the research I did in pursuit of this project, as its context. My research in 2015 informed me that the neighbourhood is unique in its recognition as Canada’s first community housing development, which took place in the 1950s. However, it is also recognized as a “notoriously ill-planned” development, featuring architectural landscapes highly conducive to criminal activity.1 Regent Park is also unique in its extreme diversity; a public report published in 2003 states that at the time it was home to 7,300 people speaking more than 70 languages, 60% of the residents were immigrants, and a third of those arrived in the previous five years.2 The same report notes that Statistics Canada classifies the neighbourhood as the poorest in the country, with less than 150 households having an income greater than $30,000 a year. That same “ill-planned” development is the landscape its residents have called home for more than fifty years. In 2006 an extensive revitalization project began, which displaces residents while new homes are in the process of being built. The new revitalization has caused great contention and controversy, however The Flux does not hope to expose this, nor does it purposefully contain bias towards one group or another. Rather, The Flux hopes to expose the state of the neighbourhood at present and provide a space for contemplation on the concepts of change, palimpsest, belonging, exile, and the home.

The shoe itself is a palimpsest of a construction boot. It bears the exact shape and components of such an article, complete with thick laces and safety footwear labels, yet its fabric is unfamiliar. For The Flux this construction boot, assembled out of materials resembling that of the chain-link fences littered all over Regent Park, acts as an allegory for change, or the revitalization, or the flux that this neighbourhood, and the rest of Toronto’s growing metropolis, is consistently experiencing. The city is always in flux. The shoe bears a label on its inside sole with the logo for the primary contractor of the revitalization, the Daniels Corporation, with the phrase “love where you live” on the bottom. When the above context of Regent Park is considered and the idea of flux is considered the phrase can hold contrasting meanings. Residents of Regent Park may react positively to Daniels’s instruction, while others may resent it. If the idea that where we live is always in flux can be accepted, where we live becomes an ever-changing landscape: we must learn to love change. The inevitability of change is widely recognized, yet we hold on to the idea that while it is inevitable, it is not currently happening. This is a fantasy, the concept of erosion being a prime example. This palimsestic shoe attempts to intrigue and cause its viewer to question what they are looking at: something familiar, yet somewhat unrecognizable in purpose.

I consider the music to be the most key element of this project. Music has an uncanny power over its listener with its ability to elicit emotions that cannot be controlled. The piece composed for The Flux has the goal of helping the projects viewer to experience multiple emotions: some that are good, bad, comfortable, uncomfortable, warm, or cold. In pursuit of this goal I composed and recorded myself singing a short melody, layering it with three-part harmony, and then re-recording the same melody multiple times with different tonalities. This was done by augmenting or diminishing certain intervals within the melody, while retaining the same rhythmic structure. This allows the piece to have distinctly similar, yet distinctly different progressions that hopefully make the listener to feel different things each time the music swells and ebbs. The piece is also ambient in certain parts, lessening its didactic influence, which also aids in its contemplative nature. This aspect of the music, combined with the separately recorded embedded city sounds helps to establish a significant soundscape for the listener/viewer.

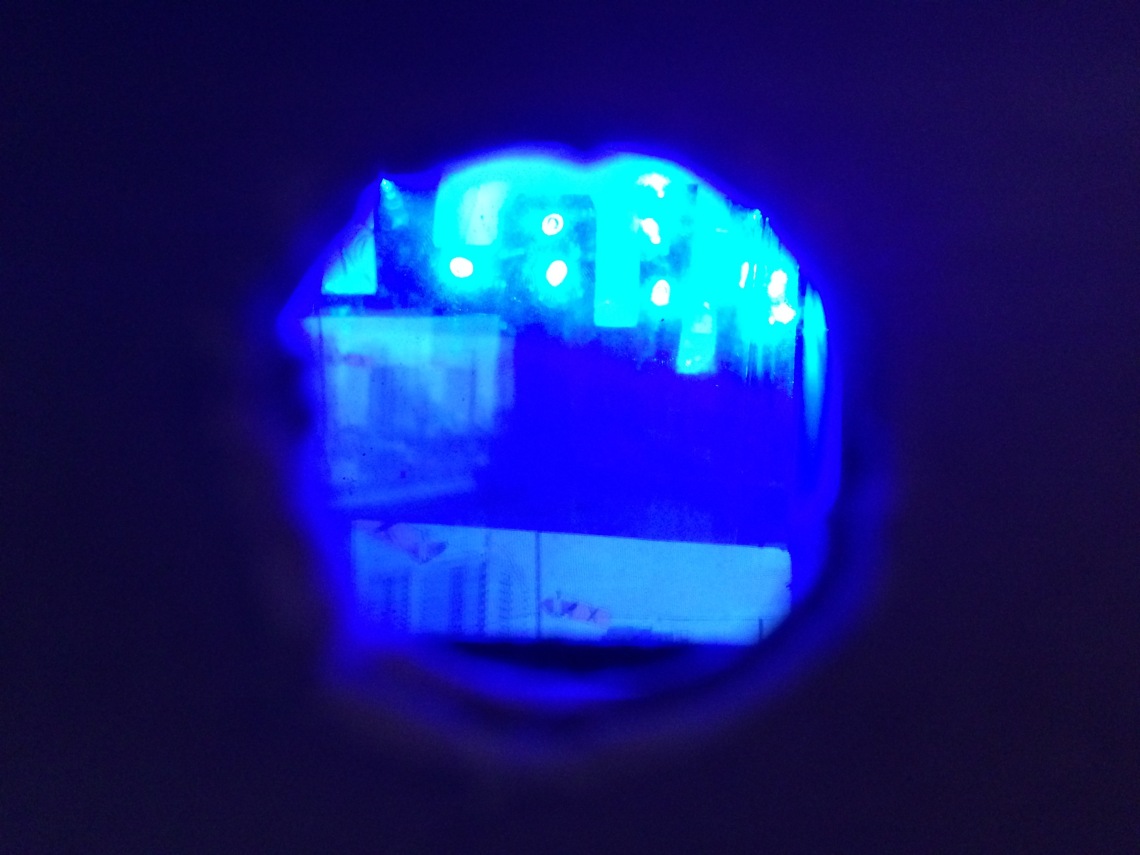

The separately recorded audio holds voyeuristic elements and hopes to provide a “flâneuristic” experience. While collecting the recordings I attempted to secretly capture people’s conversations, I pursued groups of children in the hopes of recording their laughter, and followed those with unique sounding shoes. The music sets the mood for the listener and the city sounds force them to experience the city auditorily, unbiased by the visuals I experienced while recording them. The listener experiences the city passing them by, much as the flâneur does at will. Inside the box the viewer finds a backdrop of a generic cityscape adorned with blue lights. 6 planes of glass project the video that is displayed below the viewers eyes in areas and clarities that make each “screen” different in its focus, quality, and colour. The blue lights also reflect on that various panes of glass, helping to create the illusion of more city lights. The projected video features footage I collected around and on my way to and from Regent Park. The majority of the shots are static or slow pans. This also works to create a less biased visual for the viewer to explore at will. The visual and auditory components of the box form a contemplative space, hoping, or perhaps forcing, the viewer to experience the city the way a flâneur would. Leisurely watching, listening, and thinking, with no particular goal in mind.

The process of the whole project helped to reveal the theory for me in a variety of ways. I regard my whole process as a way of me learning how to exhibit flâneury. While it was a rushed process, everything I did guided me towards what was next, almost effortlessly. From the walking exercises we did, to the readings, to each step I took in the process I was always guided by what I saw or encountered. I never knew what the project would be in the end, but the process guided me in a most comforting fashion that I felt confident in my almost flâneur-esque motivation towards what needed to be done. In this way, I attempted and succeeded in performing my understanding of the theory and ideas behind the figure of the flâneur. These ideas are not akin to my usual attitude towards tasks or projects I am working on, but were necessary for me in the completion of this project. Here, theory complemented practice. The process of making the shoe and box also helped me to understand the theory on more levels, making connections that might not have occurred if the course had not been contextualized through our readings and subsequent discussion. Artmaking forces theory to be materialized in different ways. While the theoretical ideas or interpretations behind these materializations are sometimes ephemeral, they allow their observers to make more of their own individual connections. An artmaking process such as the one I experienced in this institute helped explicate theory in more colourful ways than a book or discussion ever has, which is nothing short of eye opening. – Devon Bond